Jevons Paradox: The Problem With Chasing Efficiency

Earlier this month, 45 nations met in Versailles for an International Energy Agency (IEA) conference which set energy efficiency targets to drive down emissions. But like our New Years resolutions and for the much of the same reasons, these targets may already be out of reach.

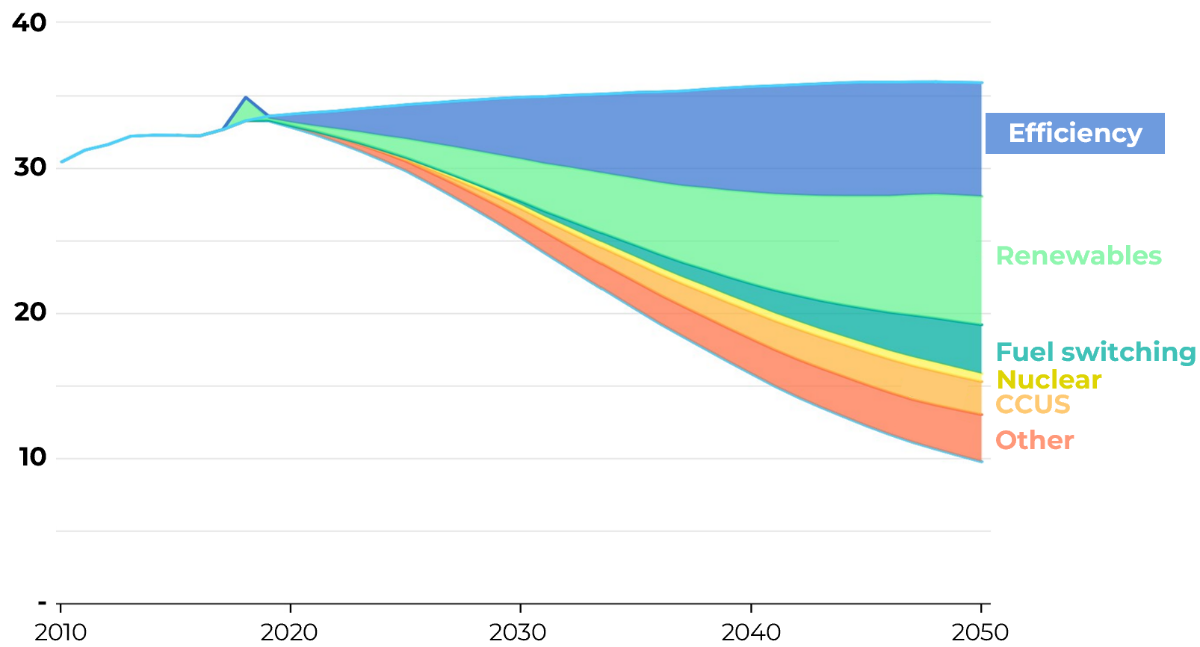

Background: One sure-fire way to reduce emissions is to do the same work with less energy. As a result, organizations like the IEA usually have energy efficiency as a key driver in their decarbonization scenarios.

- In the IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario, energy efficiency is the single largest measure to reduce energy demand.

To help encourage efficiency improvements, the IEA has been hosting regular conferences specifically on channelling their inner George Costanza and doing more with less. The Paris-based organization has said the world needs energy efficiencies to improve 4 percent per year between 2020 and 2030, double the historical average.

Energy Efficiency as part of the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario

Standing in the way of reaching these goals is unfortunately human nature, with a little quirk noticed more than 170 years ago and dubbed ‘Jevons paradox’.

Jevons paradox: William Stanely Jevons was an economist during the Industrial Revolution in England. In his 1865 book The Coal Question, Jevons noticed that after society adopted James Watt’s improved steam engine with much better fuel efficiency, the consumption of coal went up not down… the opposite of what you’d expect.

- In his best Victorian English, Jevons wrote, “It is a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.”

He essentially found that as efficiencies improved, people just found new ways to use more energy.

Then and now: Christmas home decorating

There are several factors that drive Jevons paradox, also known as Jevons effect:

- As efficiencies go up, prices come down. This leads to wider adoption and increases overall energy consumption.

- When consumers save money on energy, they then have more to spend on other goods and services, which often leads to more electricity or fuel use. To our economist readers, this is known as ‘the rebound effect’.

- Lower energy costs = innovation. New products and ideas that were uneconomic before suddenly become viable for budding entrepreneurs.

This effect can be seen across almost every sector

In agriculture, improved water use and crop productivity often leads to even more agriculture and more irrigation use. In transportation, as cars have become cheaper to own and operate, more people buy them.

- In the 1960s, the United States had 0.3 vehicles per person. By the late 2010s, vehicle ownership had more than doubled to 0.75 vehicles per person which increased overall fuel use.

Then and now: Home and vehicle ownership

It’s not all bad: In technology, as processors improve their computing efficiency, costs come down, allowing more people gain access to the internet and the global highway of digital information. Nothing brings people together like a well-timed meme.

And thanks to declining costs of refrigeration, we’re all benefiting from more varied and interesting diets.

- Us prairie folks regularly enjoy fresh sockeye salmon brought in from the West Coast, something unimagineable just a couple generations ago.

Zoom out: In some cases, energy efficiency improvements can bring about big changes. Electric motors are ~80 percent efficient compared to just 20 to 30 percent for the internal combustion engine. This suggests that an electrified transportation sector would use just a third of the energy that it uses today.

The problem with chasing efficiency is that it could end up being a red herring. Jevons paradox might mean both our cool Jetsons future is closer than we think while our climate goals are further than we need.

+Additional reading: The Versailles 10X10 Actions