Labour Productivity in Extreme Heat

If you haven’t already noticed, 2023 has been hot – less hot girl summer and more ice bath summer. Beyond wildfire response, closing schools, and having to break the bank on sunscreen, how does heat exposure affect our ability to get work done?

Background: With yet another set of heat waves threatening to push temperatures past 100°F (38°C) across parts of the US and Canada, this year continues to break heat records, with some jurisdictions planning to keep schools closed until things cool off.

- Students get an extra week of summer and parents get an extra week of wishing their kids would just go back to school already.

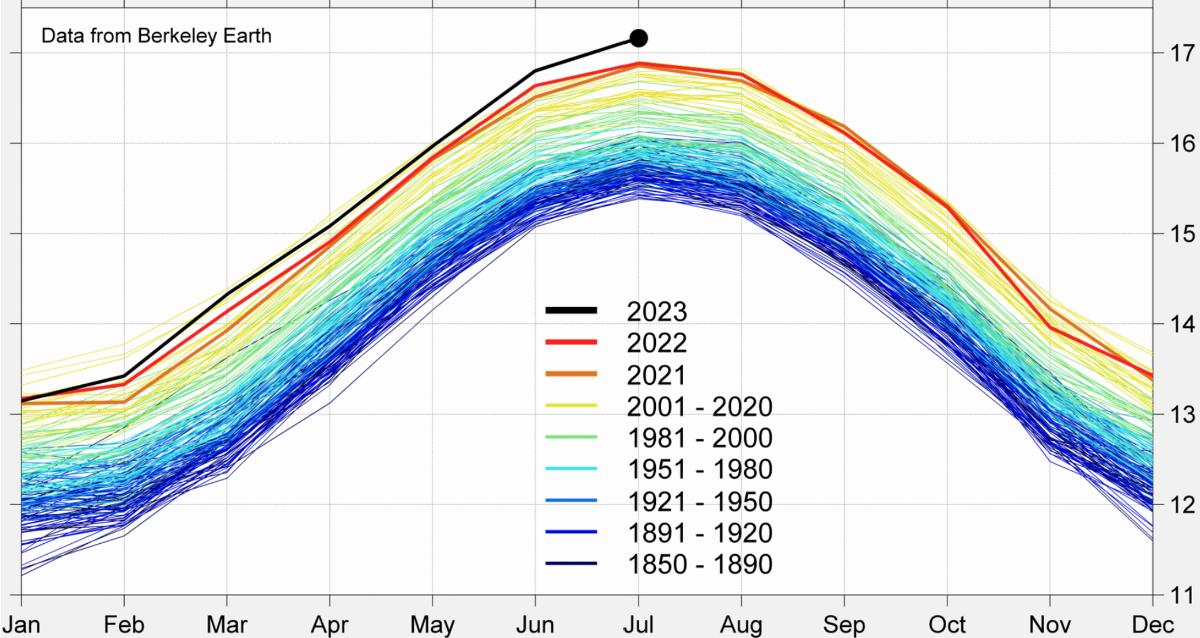

Earth’s average temperature by year, 1850-2023

degrees Celsius

According to Berkeley Earth, an open-source environmental science and analysis organization, July 2023 was officially the warmest month since climate records began in the mid-1800s (NASA agrees).

- Berkeley believes there is a 99 percent chance that 2023 will surpass 2019 as the hottest year ever.

Working 9-to-5 when it’s 95(F)

Much of the economic cost of extreme heat comes in the form of lost worker productivity. Research suggests that when working conditions exceed 90°F (32°C) worker productivity is reduced by 25 percent, and when conditions exceed 100°F (38°C), productivity can be reduced by as much as 70 percent.

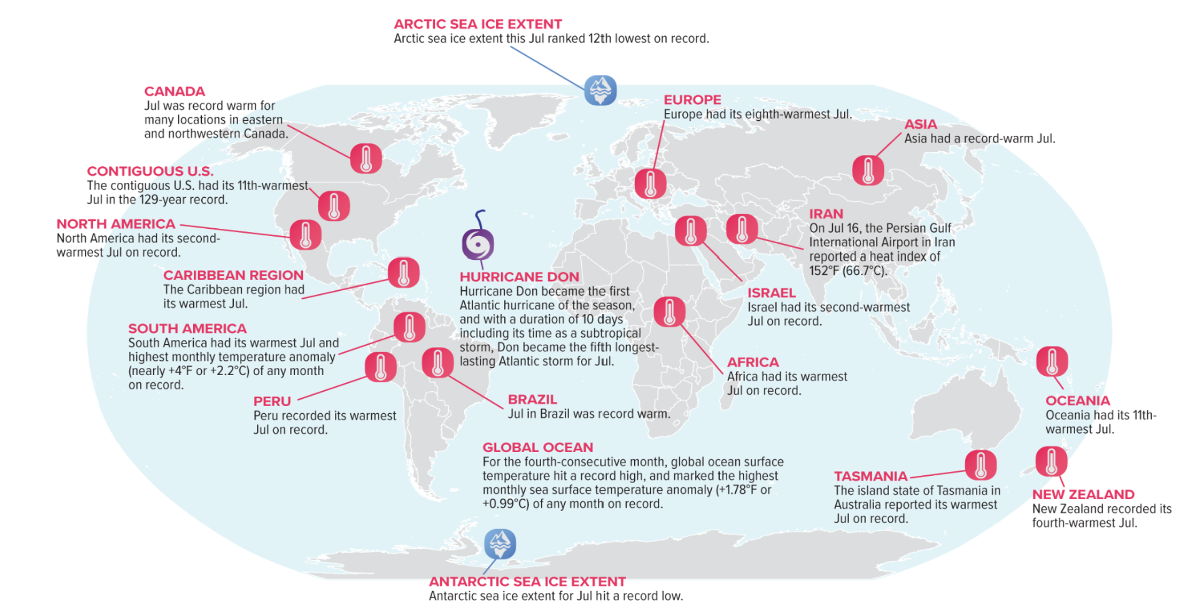

Select significant anomalies and events, July 2023

According to data from The Lancet, heat exposure contributed to over 2.5 million hours of lost labour in 2021 for the United States. For Canada, that number is closer to 40,000 hours.

Another report suggests that heat exposure contributed to nearly $100 billion in US economic loss in 2020—almost twice as much as the US Department of Energy spent last year.

- Without mitigation, that figure could double to $200 billion by 2030 and could reach $500 billion by 2050.

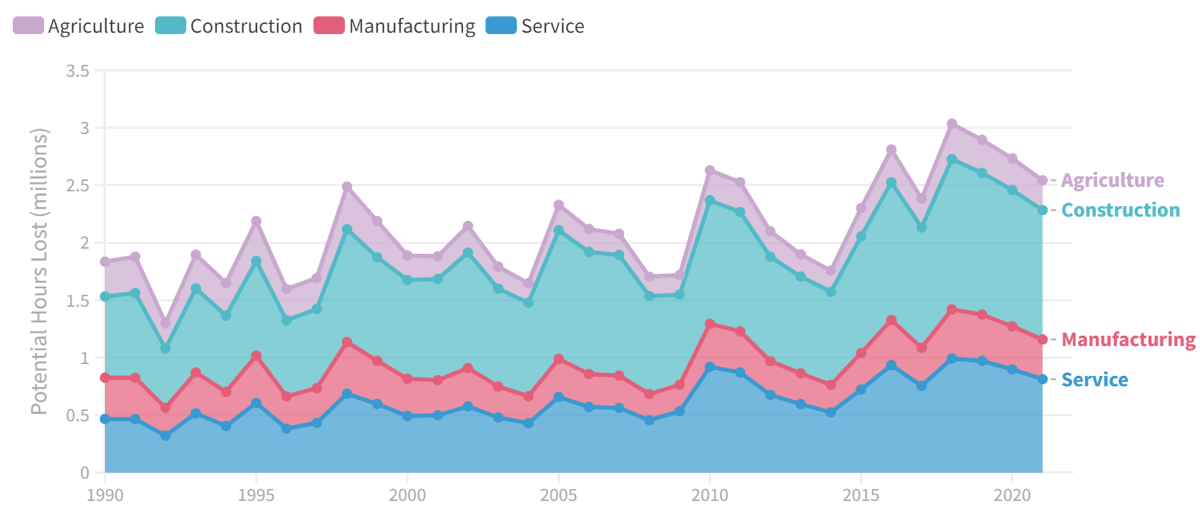

Potential hours of labour lost due to exposure to heat, United States

While outdoor workers are clearly affected by the heat, people working in delivery vehicles and indoor facilities without appropriate heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems are also impacted.

- Wearing a full set of safety gear while working in a non-air-conditioned manufacturing facility or meat processing plant is like teleporting a worker from Atlanta to Arrakis from Dune.

Heat exposure has become such a prevalent issue that UPS just agreed to install air conditioning and improved air-flow systems in all of their trucks as a result of union negotiations.

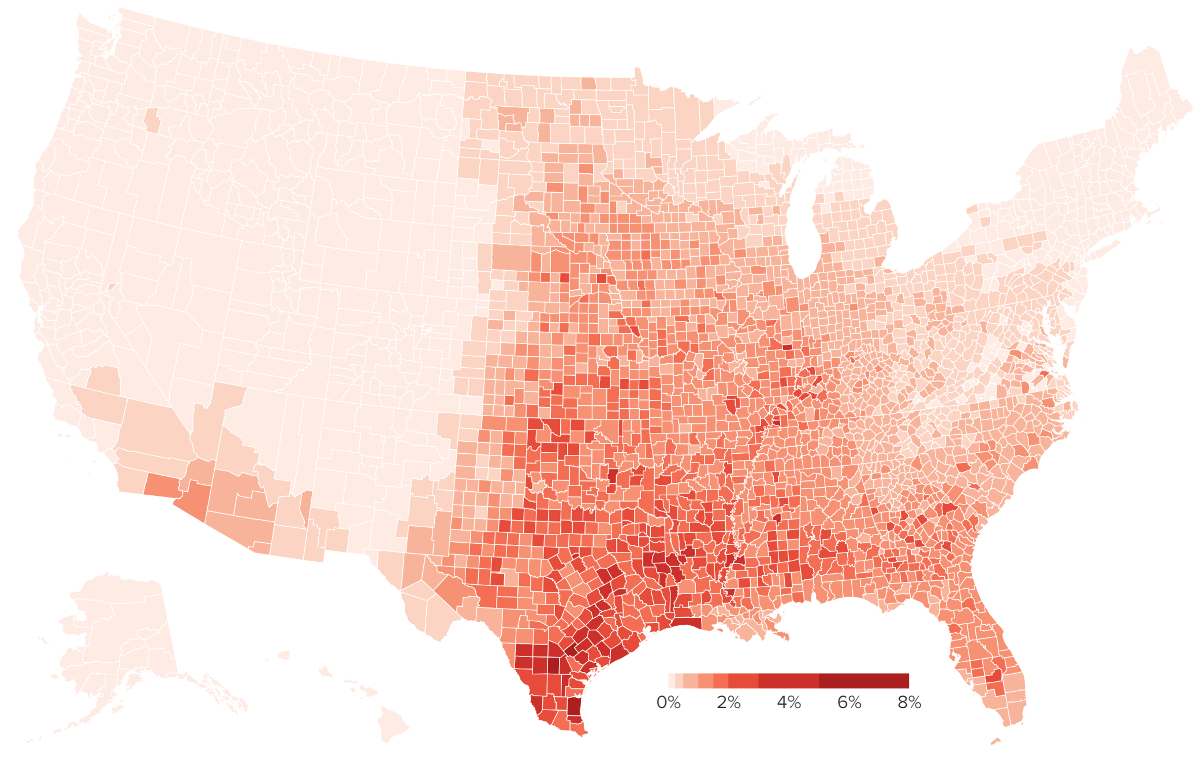

Modeled economic losses from reduced worker productivity due to human heat stress

projected percent loss in gross value added

It looks like extreme heat is going to cost a lot no matter what.

The business case: Not only does heat exposure affect labour productivity, but it can also lead to a higher frequency of safety and quality incidents along with higher rates of turnover and absenteeism.

- As extreme heat events are forecasted become more common—both from human-caused warming and El Niño climate patterns—employers who fail to provide their employees reprieve, may put their triple bottom line at risk.

On the other hand, addressing heat exposure by installing HVAC systems to keep workers happy and safe could cost employers millions—costs that many would likely get passed on to customers in the form of higher product prices.

Bottom line: With many employers already struggling to attract and retain skilled trade labour, mitigating heat exposure may just become another cost of doing business.

+Additional listening: The High Cost of Heat

++Additional reading: Trade and Labour Shortage Following Trillions in Energy Investment